1. Understanding GISTs and Malignant GISTs

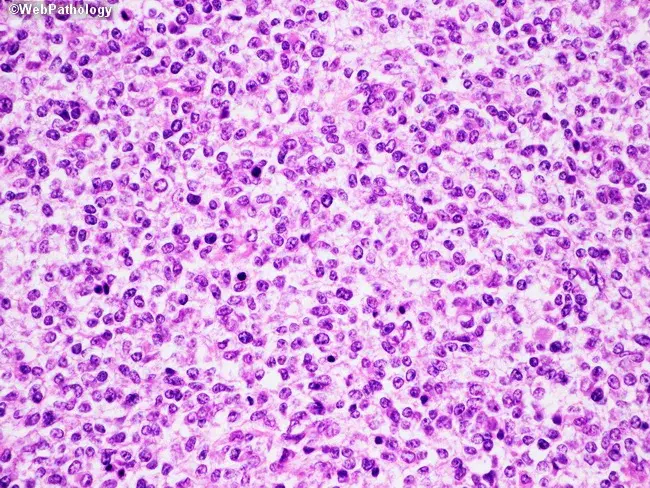

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs), which are specialized pacemaker cells in the GI tract. These tumors can occur anywhere along the digestive tract, but they are most commonly found in the stomach and small intestine. GISTs were historically difficult to diagnose because they can appear similar to other types of gastrointestinal tumors, including leiomyomas or schwannomas. However, with advancements in molecular diagnostics, particularly the identification of mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA genes, GISTs can be more accurately diagnosed.

Malignant GISTs are characterized by uncontrolled growth, the ability to invade surrounding tissues, and the potential to metastasize to distant organs. Unlike benign GISTs, malignant GISTs are more aggressive, often presenting with a high risk of recurrence and metastasis. The primary factor that distinguishes malignant from benign GISTs is the presence of mutations in genes that regulate tumor growth and cell survival, such as KIT, PDGFRA, and BRAF.

2. Metastasis Pathways of Malignant GISTs

Malignant GISTs can spread beyond their primary site to other organs, a process known as metastasis. The metastatic spread of GISTs follows well-defined pathways, primarily hematogenous (through the blood), though lymphatic spread can also occur in rare instances.

2.1 Hematogenous Spread

The most common pathway for metastasis in GISTs is hematogenous spread, meaning that cancer cells travel through the bloodstream to distant organs. The liver is the most frequent site of metastasis, followed by the peritoneum and lungs. Hematogenous spread occurs when malignant GIST cells invade blood vessels in the tumor microenvironment. These cells then enter the bloodstream and are carried to distant organs, where they can form secondary tumors. This is the most concerning route of metastasis, as it often indicates an advanced stage of disease and poorer prognosis.

Once malignant GIST cells enter the bloodstream, they can survive in circulation and eventually lodge in small blood vessels in the liver, lungs, or other organs. These cells are capable of extravasating from blood vessels into surrounding tissues, where they proliferate and establish secondary tumors. The liver is a particularly common site of metastasis due to its rich blood supply and the fact that it is one of the first organs to filter blood coming from the gastrointestinal tract.

2.2 Peritoneal Spread

In addition to hematogenous spread, malignant GISTs can also metastasize to the peritoneum. This occurs when cancer cells shed from the primary tumor and enter the abdominal cavity. Once in the peritoneal cavity, GIST cells can attach to the peritoneal lining and form metastatic lesions. Peritoneal metastasis is often associated with more advanced disease and is typically seen in patients with a poor prognosis.

Peritoneal dissemination is commonly seen in GISTs that have originated in the stomach or small intestine. The spread of tumor cells within the peritoneum can cause local symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and ascites (fluid buildup in the abdomen). Treatment of peritoneal metastasis is often challenging due to the diffuse nature of the disease within the peritoneal cavity.

2.3 Lymphatic Spread

Lymphatic spread is a less common route for GIST metastasis, but it can occur, particularly in high-risk cases. Malignant GIST cells may invade the lymphatic vessels in the surrounding tissue and travel to regional lymph nodes. Once in the lymph nodes, these tumor cells can spread further to other lymphatic regions or distant organs. Lymphatic spread of GISTs is generally less frequent than hematogenous spread, and it is often seen in tumors that are located in the upper GI tract or that have a high mitotic rate or large tumor size.

While lymphatic spread may indicate advanced disease, it does not always correlate with poor prognosis, as some patients may respond well to treatments even with lymph node involvement.

3. Genetic and Molecular Factors in Metastasis

The ability of GISTs to metastasize is influenced by a combination of genetic, molecular, and environmental factors. The majority of GISTs harbor mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA genes, which encode receptor tyrosine kinases. These mutations lead to constitutive activation of these proteins, which promotes uncontrolled cell proliferation, survival, and metastasis.

Recent studies have also highlighted the role of BRAF mutations in some GISTs, particularly those that do not harbor KIT or PDGFRA mutations. These mutations contribute to aberrant signaling pathways that can drive tumor growth and metastasis. Additionally, mutations in tumor suppressor genes, such as SDH (succinate dehydrogenase), have been identified as playing a role in the metastatic potential of GISTs.

Molecular profiling of GISTs has provided valuable insights into the biology of these tumors, helping to predict the likelihood of metastasis and response to treatment. For instance, high levels of KIT expression and certain mutations, such as those in exon 11 of the KIT gene, have been associated with a higher risk of metastasis.

4. Clinical Features and Diagnosis of Metastatic GISTs

Patients with metastatic GISTs often present with nonspecific symptoms, which can make early diagnosis challenging. Common symptoms of metastatic GISTs include abdominal pain, weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, and the development of palpable masses. When metastasis occurs, patients may also experience symptoms specific to the affected organ, such as liver enlargement or shortness of breath in cases of lung metastasis.

The diagnosis of metastatic GIST is typically confirmed through imaging studies and biopsy. Common imaging techniques include:

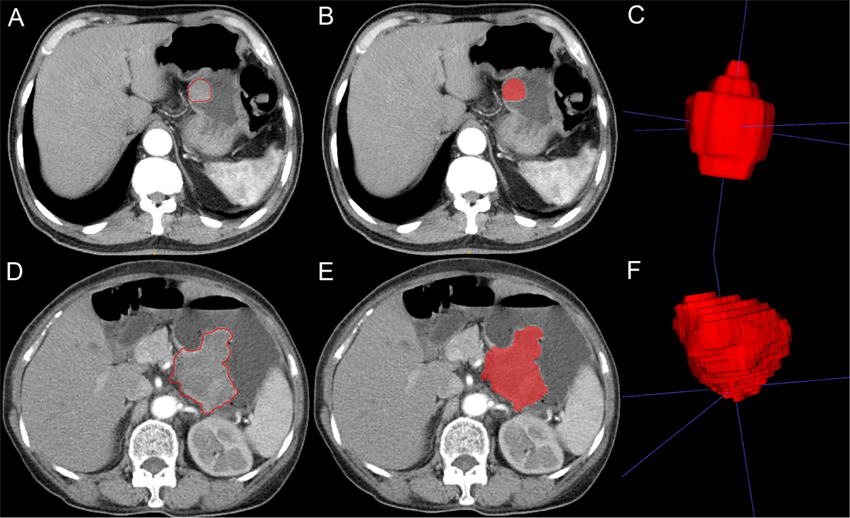

- CT Scans: High-resolution CT scans are used to assess the size, location, and extent of the primary tumor and any metastatic lesions in the liver, lungs, and peritoneum.

- MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging is useful for evaluating soft tissue involvement and can provide detailed images of the liver and abdominal cavity.

- PET Scans: Positron emission tomography (PET) scans are used to detect metabolically active metastases and to monitor treatment responses.

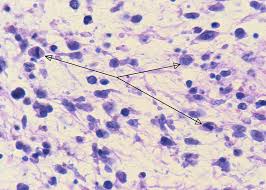

- Endoscopy and Biopsy: In cases where the primary tumor is located in the gastrointestinal tract, endoscopy may be used to obtain tissue samples for histological analysis and confirmation of malignancy.

Once diagnosed, the metastatic spread of GISTs is staged according to established guidelines, which help guide treatment decisions and prognostic evaluation.

5. Treatment of Metastatic GISTs

The management of metastatic GISTs involves a multidisciplinary approach and may include surgery, targeted therapy, chemotherapy, and supportive care. The treatment strategy depends on factors such as the location of the metastasis, the extent of disease, and the patient’s overall health.

5.1 Surgery

Surgical resection remains the primary treatment for localized GISTs and isolated metastases, particularly when the tumor is confined to one organ (e.g., the liver or lungs). Surgical removal of both the primary tumor and any metastatic lesions can significantly improve survival, especially in patients with limited metastatic disease. However, complete surgical resection is often not possible in patients with widespread metastases or peritoneal dissemination.

5.2 Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapies, particularly tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), have revolutionized the treatment of metastatic GISTs. The most commonly used TKI for GIST treatment is Imatinib (Gleevec), which specifically targets the KIT and PDGFRA mutations commonly seen in GISTs. Imatinib has been shown to reduce tumor size, slow disease progression, and improve overall survival in patients with metastatic GISTs.

In cases where GISTs become resistant to Imatinib, second-line therapies such as Sunitinib (Sutent) and Regorafenib (Stivarga) may be used. These drugs are effective against tumors that have developed resistance to Imatinib and target additional pathways involved in tumor growth.

5.3 Chemotherapy

Traditional chemotherapy is generally not effective in treating GISTs due to their molecular characteristics. However, in some cases, chemotherapy may be used in combination with targeted therapy or in patients who do not respond to TKIs. Drugs like doxorubicin and ifosfamide have been used experimentally, but their efficacy is limited.

5.4 Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, is an emerging area of treatment for metastatic GISTs. While still in the experimental stages, studies suggest that immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab could offer a new avenue for treating GISTs, particularly in cases where traditional therapies have failed.

5.5 Palliative Care

In cases where metastatic GISTs are not amenable to curative treatment, palliative care becomes an important aspect of management. The goal of palliative care is to alleviate symptoms, manage pain, and improve quality of life for patients with advanced disease.

6. Prognosis and Survival Rates

The prognosis for patients with metastatic GISTs depends on several factors, including the size and location of the metastases, the molecular characteristics of the tumor, and the patient’s response to treatment. Overall, the prognosis for metastatic GISTs is poor, but with early detection and appropriate treatment, some patients can live for several years with controlled disease.

Studies have shown that patients who respond to Imatinib therapy and those with isolated metastases may experience longer survival rates, while patients with widespread metastasis or resistance to treatment generally have a poorer prognosis.

Malignant GISTs are aggressive tumors with a propensity for hematogenous and peritoneal metastasis. The pathways of metastasis, along with the underlying genetic mutations that drive tumor progression, significantly influence the clinical course of the disease. Targeted therapies, particularly tyrosine kinase inhibitors, have dramatically improved treatment outcomes for patients with metastatic GISTs. However, the challenges of drug resistance and the need for new therapeutic approaches highlight the importance of ongoing research in this field. By better understanding the molecular mechanisms behind metastasis, new, more effective treatments can be developed, improving survival rates and the quality of life for patients battling metastatic GISTs.